11:14 PM 3 JANUARY 2020

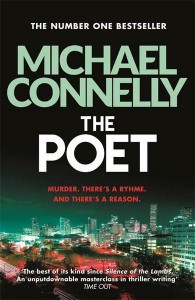

“Death is my beat…” is the kind of dramatic opening at which Michael Connelly excels and it’s a fitting introduction to the main character of this 1996 novel, ‘Rocky Mountain News’ reporter, Jack McEvoy. I should perhaps stress that this is NOT a Harry Bosch detective story. Notwithstanding my intention to run down the lengthy Bosch series of novels, my learned friend and aficionado in such matters advised there was value in this (not so short) diversion that would see seeds sown, to be reaped later. Time will tell. However, the sure-footedness of the author’s writing style certainly made this standalone companion to my literary pilgrimage, worth paying homage to. Indeed, there are parallels between the detective and the journalist and just as Harry Bosch has previously found himself enmeshed in the FBI, so in this novel, it is the turn of Jack McEvoy to work alongside the Feds, in an investigation spanning a number of states.

The catalyst had been the death of Jack’s twin brother. The lead investigator on a horrific murder case, Detective Sean McEvoy had allegedly committed suicide, overwhelmed by the attendant emotional trauma. The evidence had been weighed quickly, to turn an embarrassing page for the local police department, only Jack wasn’t buying it. What if, instead of assuming suicide, it was assumed that Sean McEvoy was the victim of a homicide? Could the evidence support such a radically different interpretation? The police aren’t the only agency with investigative resources and by pulling hard on the loose threads, Jack begins to unravel a whole world of pain.

Not only is the dynamic flow of the plot reminiscent of the Bosch novels, in Jack McEvoy, the author has also embedded some very familiar traits. Intelligent, but stubborn, rebellious, but loyal, determined, but at times naive, there is something very satisfying about the maverick character cocking a snook at authority and in so doing establishing his integrity. Of course, as a former crime reporter for the LA Times, Michael Connelly is well-placed to lift the lid a little on the role of the investigative journalist and the inherent tensions between the guardianship of the public’s ‘right to know’ and those clandestine operatives tasked with keeping the public safe from harm, on a ‘need to know’ basis. With trust on both sides in short supply, the author also has fun with it, in the inevitable romantic incursion across boundaries. Though this lighter plotline perhaps eases the discomfort, which flows from the disturbing portrait of a clinical serial killer.

All-in-all a very satisfying, but challenging read and the sequel (‘The Narrows’) comes in at number ten in the Harry Bosch ‘hit parade’. In fact, last week the third book in the ‘Jack McEvoy series’ has been announced (‘Fair Warning’ due out in May 2020). This intertwining of characters and series is turning my simple trek through an interesting body of work into something of an odyssey, but the journey is made all the more interesting for it. Still, I am also indebted to my Twitter buddy @JoeBanksWrites who is up ahead on the reading list climb, like my very own literary sherpa! Next stop for me, Book 5, “Trunk Music” (1997). See you at the top!