1:06 AM 2 JANUARY 2018

Using a novel to highlight invisible social issues, such as runaway teenagers, taking flight as a consequence of factors such as domestic violence, gang culture and parental rejection is a tricky business. For example, who knew “one in ten run away from home before they reach the age of sixteen, a massive 100,000 every year”? It’s a fairly damning statistic, which says much about British society and an apparent incapacity to protect vulnerable young people. Moreover, “two thirds of children who run away are not reported to the police.” Still, against this rather bleak backdrop, Jane Davis has constructed a subtle plot, which does far more than merely generate pathos. Indeed, JD has also sought to establish that this is not a problem solely besetting some poverty-stricken underclass, but rather an issue that crosses mundane social boundaries and ‘runaways’ might therefore be seen as victims of an extreme degree of family separation.

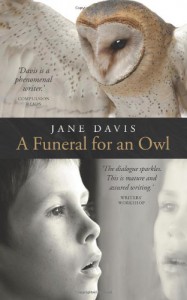

‘A Funeral for an Owl’ centres on history teacher, Jim Stevens, who works at an inner city high school, but originates from the nearby council estate and though the vagaries of social mobility have enabled Jim to move literally to the other side of the railway tracks, he has not strayed far from his roots. When a violent incident at school sees Jim hospitalised, colleague (‘Ayisha’) is drawn into the clandestine support he has been providing to one of his pupils (‘Shamayal’) and Ayisha’s own integrity, in the face of strict policies and procedures, is challenged.

Ayisha has benefitted from a stable family upbringing and though struggling with the expectations of a distant and demanding mother, she has little insight into the profound hardships experienced by some of her disadvantaged pupils, away from school. And so, while Jim languishes in a hospital bed, the story alternates between examining Jim’s past experience, which culminated in his being stabbed and the very pressing present, which finds Ayisha discovering that doing the ‘right thing’ can take courage and a sense of bewildering isolation.

In spite of his inner city upbringing, ten year-old Jim is into birdwatching and this egregious pastime enables the boy to connect with the troubled Aimee White. Two years his senior, Aimee is destined to attend the all-girls school designated by her wealthy parents, but for the intervening six weeks of the summer holidays, the pair fashion a poignant relationship, which bridges their respective worlds. Almost spookily prescient, Aimee observes that “Indian tribes believe owls carry the souls of living people and that, if an owl is killed, the person whose soul they’re carrying will also die.”

Later, the geekiness of Jim’s birdwatching also captures Shamayal’s imagination and there is symmetry too, in Jim’s burgeoning relationship with Ayisha.

However, what stood out most for me in this book was the crafted writing, in which JD changes gear so smoothly that the journey was simply a pleasure and over all too quickly. The plot was deceptively simple and yet the characterization of the protagonists was insightful and interesting (I especially enjoyed ‘Bins’ the estate eccentric, who is curiously invisible) and made the story eminently plausible and readable. Clearly the book is not targeted solely at young adults and as with a lot of good fiction, the food-for-thought it provides is rightly taxing. As a social worker myself, it would be easy to criticize the rather neat conclusion, which perhaps sanitizes the ‘messiness’ that attends typical family life, but that would be churlish and miss the point. The adage that ‘it takes a whole village to raise a child’ is at the heart of this book and we all need to do our bit…